I share two stories when people ask about my mom. The first, from when I was around 7, is about the time she shoved soap in my mouth after I said a swear word while we were at a friend’s house. The second, from a few years later, was when she reached into the back of the car, while driving, and smacked me in the leg after I was disqualified in a swim race. She wasn’t mad about my mistake but annoyed about our delayed departure to visit my grandparents in Boston.

I have yet to forgive her.

My mom swears like someone who spent one of her formative years at a bar. In third grade, I had a friend over for a playdate, and he witnessed an argument between my mom and one of my sisters, that he later told me contained more swear words than he had ever heard in his entire life. A few years later, my mom got lost while driving me and a few teammates to a hockey game on Long Island and spent 30-minutes swearing at the traffic, the coach who had provided the directions, all of us in the car, and for some reason, my dad, who was at work. She keeps up this legendary language even at the age of 81. Last month, my six-year-old son, Aksel, and I were video chatting with her when she dropped two f-bombs in one sentence. What caught my attention, though, was that my dad was on the receiving end of only one of them.

On family road trips, we never made it more than 30 minutes before having to turn the car around because my mom had forgotten something. Her medicine, sneakers, and curling iron would have won family bingo, with forgetting to turn off the stove, turn on the sprinkler system, or lock the door also faring well. I am pretty sure she made us turn around on the trip to Boston the afternoon of my swimming disqualification, too. After returning home, and not finding her forgotten items in the house, she would unpack the car and find them somewhere in her bag. At some point, our family built these delays into our departures. I am sure my dad still does this today.

While my mom’s behavior should have barred her from ever holding me accountable for similar transgressions, that’s not the only reason I have yet to forgive her.

The soap in my mouth only seemed to cement curse words into my vocabulary. After nearly ten years together, my wife, Vicky, is still shocked at how I incorporate swear words when describing the mundane. It’s never, “it’s raining quite hard,” but “holy sh*t, it’s f*cking pouring.” Though, unlike my mom, I try not to swear in front of Aksel. Instead, I use phrases like faluky for f*ck or shanaky for sh*t. So, when I see someone driving too fast when Aksel and I are playing in the driveway, I yell, “Slow the faluky down!” Aksel uses these words as well, but more often chooses a German swear word to express his frustration as those don’t seem to count as curses.

Like many teenagers, my mom was enemy number one. Some of the ill will was warranted—she was a serious snoop. The first thing I remember her finding, in the third or fourth grade, was a class list that my friends and I had marked up labeling who was cool and who wasn’t. I got a stern talking to and spent some time in my room, which, as I got older, my mom loved to sneak around. Chewing tobacco, failed Science tests, you name it she found it. Except for the beer cans that I learned to arrange on my shelf like an art exhibit.

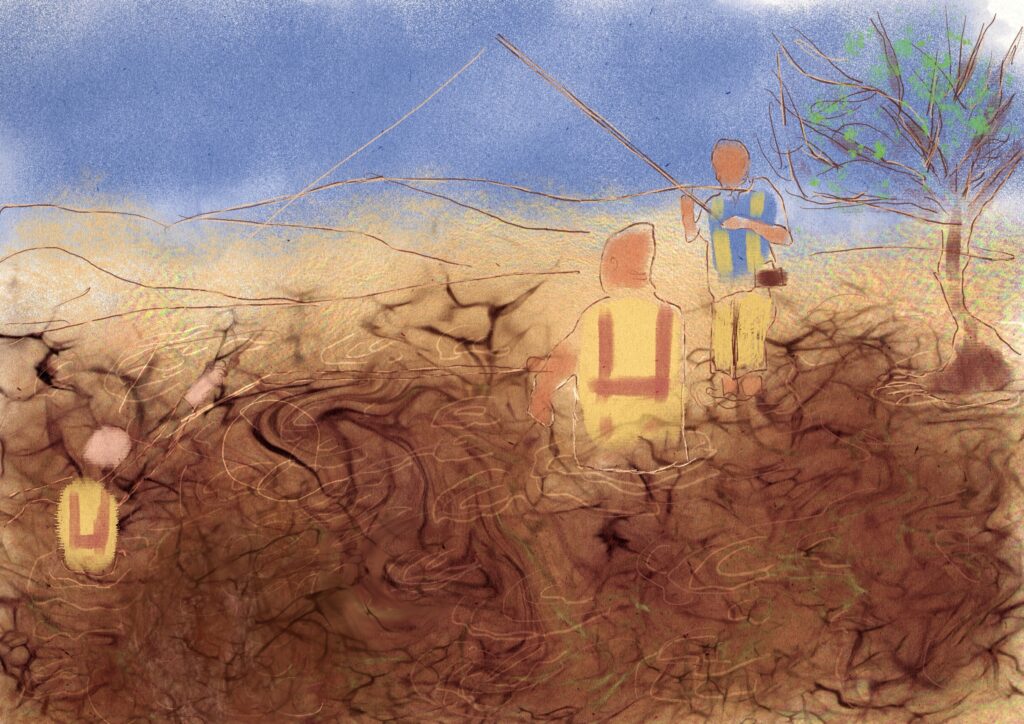

Most of my hostility, however, was not merited. My mom attended nearly every event I ever had, even if I was warming the bench, had three lines in a play, or was singing “Oh, What a Night,” with my chorus, again. After attending hundreds of my older siblings’ sporting events, recitals, and plays, she could have easily passed on a Friday night hockey game on Long Island or a Saturday matinee, but she never did. When friends would make caustic comments that she was everywhere—chaperoning class trips, working at the school bookstore, or bringing snacks to sporting events—I laughed along with them. I always wanted to ask where their moms were but never had the courage to do so.

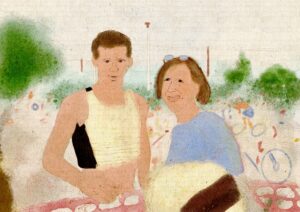

When I started competing in triathlons and running races, in my 20s, my mom continued her steadfast support. She drove me to my first marathon on Cape Cod, during the fall of my senior year in college, and then drove me back to Boston, the wrong way from her house, later that day. The next summer, she was at the start line of races throughout the tri-state, and two years later, took a five-hour train ride to Lake Placid, N.Y. to watch me complete my first Ironman. I now appreciated her appearances and sought her out immediately after crossing the finish line. Her support continued when I started coaching high school sports. She thought nothing of spending a Friday night in a freezing ice rink or a Saturday afternoon in the rain watching me coach.

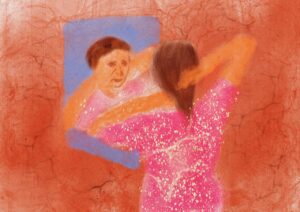

These are the stories I should share about my mom. But, like her, I often express myself contrary to how I feel. For her, it was expressing shock and then spite every time I moved away from home or chose a different path from my siblings. After arguments, I would leave her house or hang up the phone upset and angry but more than that, confused. Later, I would hear my mom’s real sentiments from one of my sisters, with whom she had spoken to immediately after we had argued—that she only wanted the best for me and that her anger only stemmed from her love. As I have learned more about my mom’s upbringing, she really did spend most of 5th grade at a bar with her alcoholic mother, her reactions to me leaving the healthy home she built over decades of hard work are more understandable.

With Aksel at the age where he has more explicit memories, I wonder what stories he is going to share about me.

The night before Aksel’s first swim class, two years ago, Vicky and I explained to him that it would be a 30-minute drive to the pool, he would have to take a shower before getting in, and he would eat dinner a bit late. What we didn’t explain to him was that this was a swimming course and not free play. For 45 minutes, I watched in horror as Aksel disregarded the teacher’s instructions and spent most of the time splashing around in the opposite side of the pool from the other kids. I didn’t say anything to Aksel at the end of the class but vented when we left the changing room, and the eyes and ears of the other parents. On the ride home, I continued pointing out everything he did wrong and how disappointed I was.

Later that evening, I realized that I had not told Aksel that he was taking a lesson and that there would be a teacher to whom he had to listen. At breakfast the next morning, I apologized to him for my behavior. I didn’t smack Aksel in the car, but it sure felt like it.

He might also share about the three years we have spent together since I quit my job to be a stay-at-home dad, when he was three-and-a-half. I imagine these stories will include more implicit memories about our fun-filled days hiking and skiing in the mountains that surround our house, but it might also include specific recollections of secretly singing the alphabet, filled with naughty words, as we bike around town or play in his bedroom.

Last Saturday, I rode in the Alpenbrevet, an annual bike event in the Central Swiss Alps. As I pulled into Ulrichen, a small town in the next valley from our house, exhausted from riding nearly 70 km and climbing over 2000 meters, I saw Vicky, Aksel, and my parents standing on the sidewalk cheering me on. They snapped a few pictures, gave me some food and water, and then shouted words of encouragement.

My mom’s classic “Go Tommy,” which she has been shouting for decades, made me smile, and provided that extra push to get me up the last climb of the day. Two hours later they all greeted me at the finish line with high-fives and hugs!

I received some troublesome traits from my mom including a painful bunion, unsightly varicose veins, and horrible handwriting, but I also got her beautiful blue eyes and the understanding that your family, especially your children, is the most important thing in your life.

About:

Tommy Mulvoy is an American expat living in Andermatt, Switzerland with his wife, Vicky, and son, Aksel. After teaching high school for nearly 20 years, he is now a stay-at-home dad. His published writing, which focuses on parenting, mental health and sports, can be found at tommymulvoy.com.

Image 1 – Original Photography by Andrej Lišakov via Unsplash, Image 2 & 4 – Original photography provided by author, Image 3 – Original Photography by Porapak Apichodilok via Pexels. Illustrations by Scalar Comet.